reviewed by Dan Barth

From DHARMA beat, issue 10, Spring 1998

For Jack Kerouac fans and enthusiasts the publication of Some of the Dharma

is a major event. This book that had been often rumored and mentioned is now a

reality. We can finally hold it in our hands and read the words Kerouac wrote

more than 40 years ago after his meditations in the Carolina woods, in Mexico

City, Berkeley, San Francisco, Richmond Hill, Long Island and under the Brooklyn

Bridge. It brings to mind Kerouac’s line in his fantasy "The Early History of

Bop," --- "You can’t believe that bop is here to stay . . . that it is real."

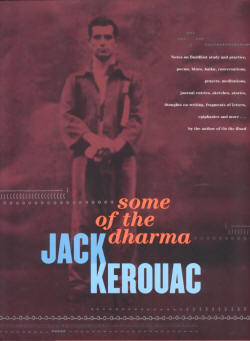

Some of the Dharma is here, it’s real, with a picture of handsome young Jack in

coveralls on the cover, standing straight to tell it like it is. Empty and

awake, a brakeman on the universal freight.

It should be said right off that this book about large Truths and about the

annihilation of the discriminating, duality-making ego-self is not nearly as

fast or enjoyable a read as Kerouac’s "true story novels" about himself and

other discriminating ego-selves. The Dharma Bums and Desolation Angels, for

instance, present many of the same Buddhist concepts as Some of the Dharma but

they also have story and characters to keep the reader interested. Relying on

Buddhist musings alone, Some of the Dharma requires a reader to be in a more

meditative frame of mind. There is no plot, no story, no "mad to burn"

characters, but there is much of the same wonderful word magic found in all of

Kerouac’s work. Interspersed with dharma talk there are many poems and other

gems of Kerouacian wordplay. And there is a goal to all of Jack’s meditation and

discourse: "From out of this you emerge with loving-kindness, compassion,

gladness and equanimity."

There are many ways to approach this somewhat daunting book and each reader

will likely adopt his or her own strategy. Some will decide to delve here and

there at random. Others may give it a cursory read and come back later for more

depth. And some may want to read it in conjunction with the letters of the same

period, 1953-1956, or the other Kerouac books that it most closely relates to

--- Visions of Gerard, Mexico City Blues, Scripture of the Golden Eternity, The

Dharma Bums, Desolation Angels, Book of Dreams, Pomes All Sizes. I approached it

as a kind of meditation, to be taken slowly, in small doses, savored and

contemplated.

Every now and then in the gloom of daily living

and daily complaining and daily unhappy horror I get a twinge of joy remembering

the original Dharma of Pure brightness, an ancient ecstasy is hiding in the

my-mind-middle-Room-Poorhead (p. 236)

The Kerouac we encounter here is mostly the earnest childlike Buddhist, like

Ray Smith in The Dharma Bums, who wants to "save all sentient beings from

suffering and to bring them to eternal happiness." More than any other Kerouac

book this one seems apart from his everyday self of storytelling and literary

ambition. It is Kerouac’s meditation self that is put on the page here. This

book started in December 1953 as notes on Buddhism to Allen Ginsberg. After

promising to send Allen the 100-page manuscript, Jack wrote: "I haven’t sent you

the Notes on the Dharma because I keep reading it myself, have but one copy,

valuable, sacred to me . . . --- Besides it is not finished, I keep adding every

day. . . " Indeed there are several times in this book where Kerouac writes as

if he is done with it, only to pick it up again not long after. It’s almost like

he was not doing it himself, was simply transcribing transmissions received

during meditation and study.

Of course there’s a certain paradox inherent in this "wisdom" book by

Kerouac, a man who drank himself to an early death. It becomes a "do as I say

not as I do" kind of teaching, but that does not negate its validity or negate

the poignant fact that during the three-year period of his life while he was

writing Some of the Dharma, Kerouac was practicing Buddhist dhyana (meditation)

and achieving some happiness and peace of mind. Again the idea of "transmission"

suggests itself. For three years Kerouac was picking up Buddhist wisdom on an

open channel; then it stopped. By 1959, as he wrote to Philip Whalen: "Myself,

the dharma is slipping away from my consciousness and I can’t think of anything

to say about it anymore."

I’m not as big a fool as I used to be, I’m a

smaller fool---- (p. 270)

Reality isn’t bleak nor can it be said to be

non-bleak either . . . (p. 323)

MY OWN PROVERB: Vest made for flea will not fit

elephant . . . (p. 344)

Kerouac’s dharma talk can be confusing-sometimes sayings, aphorisms, advice;

sometimes the multi-faceted Indian Hindu trappings of Mahayana Buddhism;

sometimes the liberating, confuse-the-rational-mind quality of zen koans. From

out of this jumble certain themes do emerge. One recurring theme is that all

sounds are part of "the One Transcendental Unbroken Sound." The corollary to

this is that all objects and activities are "d.f.o.t.s.t."---different forms of

the same thing (or sometimes "different forms of the same holy emptiness.")

Frequently all phenomena are seen as "visionary flowers in the air" or "a dream

that has already ended." A dominant theme is taken from the Diamond Sutra: "Form

is emptiness, emptiness is form" or "everything is empty and awake." At one

point Kerouac writes: "ROCKY MOUNT NEGRO SHACKTOWN, Stopped, wrote this on lamp

pole:-’Everything’s Alright--form is emptiness & emptiness is form--& we’re here

forever--in one form or another--which is empty’." Imagine the down home folks

of 1956 Rocky Mount, North Carolina trying to make heads or tails of that! These

several themes and motifs all recur, overlap and interplay kaleidoscopically as

Kerouac explores Buddhism in relation to his everyday life. It goes on and on

and on and on. (Did you think Some of the Dharma would be some quick little

light read? Think again, oh dweller in illusion.)

Another way to look at this book, and Kerouac’s Buddhism, is as an attempt to

find a way to keep from drinking himself to death. He writes: "I don’t want to

be a drunken hero of the generation suffering everywhere with everyone. I want

to be a quiet saint living in a shack in solitary meditation of universal mind."

But we know what happened. Jack keeps making his desert hut plans-retreat, plain

food, no drinking. It’s a sad effort, touching, triste. But the paradox of his

alcoholism is also present here. He says: "I’ve had my highest visions of

Buddhist Emptiness when drunk."

There are lots of words of wisdom offered, lots of Buddhist concepts juggled

and played with. As the book goes on Jack often seems confused by it all. It’s

as if he thought nirvana would be as easy as two or three months of meditation.

He begins to realize this is not the case, that his fate is inescapable, already

mapped out - the Duluoz legend - with Buddhism just a temporary refuge.

A picture emerges of Kerouac, like Christ, just here to fulfill his

destiny-to write "the ONE BOOK"---struggling and fighting against it at times,

but really always just fulfilling his Fate. It’s interesting that this

three-year Buddhist religious phase of Jack’s life took place in almost exactly

the same years of life, early thirties, that his childhood Catholic Christ is

said to have lived his public religious life. Jack’s imitation of Christ, best

he knew how. He did alright and was a good writing Buddha for awhile, practicing

dhyana, cultivating virtue, reading sutras, writing emptiness.

Obviously Kerouac was fascinated with all the words and concepts of oriental

religion --- the six paramitas, the four transcendental virtues, the ten bhumis,

crotopanna, sakradagamin, anagamin, kshanti paramita, and

annuttara-samyak-sambhodi. Maybe all his Buddhism was simply stockpiling ammo

for his wordslinger arsenal. In Buddhism Kerouac found new words, another

language, new ways to say all the things he felt and knew. French, Spanish,

English and prajna paramita. Always in love with the sound of language, Kerouac

was knocked out by all the manomayakaya and acinty-paranima-cyuti word

combinations he found in Buddhist texts.

And much of this time Kerouac is in actuality (in this dream of life) living

with his mother and sister, brother-in-law and nephew in Rocky Mount, North

Carolina and meditating in the woods with dogs---"long wild samadhis in the ink

black woods of midnight, on a bed of grass." No doubt (and no wonder) his

relatives got tired of all his Buddhist talk. It definitely was not all dharma

and bliss. Read his letters of the same period. This is post-On the Road,

pre-Dharma Bums Kerouac, away from his wild pals, in quiet and serious study of

Buddhism. But this period is getting him ready for the friendship and joy of

Dharma Bums.

I’m wondering if this is one of those books that will be more talked about

than read. It is certainly a lovely book and a wonderful publishing

achievement-as near as possible a facsimile of Kerouac’s original typescript.

But for anyone without a strong interest in Kerouac or Buddhism, or both, it is

a book they may not have the patience to read- 420 pages of Kerouacish ramblings

on Buddhism. And the print is small. I can’t help but wonder if this book is

more document than art. In editing Kerouac’s letters, Ann Charters has been

accused of cutting too much. The editor of this book, David Stanford, may have

to answer for leaving in too much. Perhaps a more readable book could be created

by cutting some of the repetitive Buddhist ramblings. Or maybe a good publishing

strategy would be to issue it in several smaller volumes, like the small

Shambhala books on Eastern religions, or like R. H. Blyth’s Zen and Zen

Classics. I think future editions might also be made more manageable by

including an index, and perhaps a bibliography of Buddhist books that Kerouac

was reading. For now though, we’ll be grateful for what we have. No matter what

happens next I think it’s good to have the book issued first in it’s entirety, a

mother lode that may be a long time playing out.

The book ends in March of 1956. Kerouac is getting ready to take off for

Mexico again, then San Francisco and Desolation Peak and on to fame and alcohol

in the remaining years of his life. Buddha Jack of the dogs and cats, not

different from emptiness, listening to the sound of silence, in love with the

sound of words. It ends with a picture of one of Jack’s angel dove ghosts, a

truly amazing wonderful compilation book journey meditation on Buddhism and

emptiness. Samadhis and Samapattis and Dhammapadda and Innumerable Aeons and

Chilicosms of Blinkforths and Blablahblah wrote old Jack in his cups with a

kitty walking down the path on the way that is not a way to the gate that is not

a gate using words beyond words to express silence. Amen. So be it. Ainsi soit

il. Thus it is. Svaha! Grah!

(copyright 1998 by DHARMA beat and Dan Barth)

Also, read Dan Barth's review of "The Awakener" by Helen Weaver. |